by ibakarr | Aug 11, 2016 | Uncategorized

The long drawn out trial of The State v Afsatu Kabba, former Minister of Fisheries and Marine Resources, arguably the most publicized corruption-related trial in Sierra Leonean jurisprudence finally came to an end on Tuesday, 12thOctober instant in the High Court of Justice presided over by Justice Samuel Ademusu. The accused, who was standing trial over misappropriation of public funds and abuse of office contrary to sections 36(1) and 42(1) respectively of the Anti-Corruption Act 2008 (as amended) and who was stoutly defended by a battery of seasoned legal practitioners, was convicted on five of the seven counts that she had been arraigned in court for. After delivering the marathon judgment that lasted for about two hours in a tensed courtroom convicting the accused on counts 1-5 which dealt with the misappropriation of public funds and acquitting her on counts 6-7 which had to do with abuse of office, the learned Judge asked whether the defence team had anything to say before proceeding to her sentence. In his submission, the lead defence counsel, Blyden Jenkins-Johnston, was most obliged in asking the presiding Judge to temper justice with mercy. He further pleaded with the Judge not to impose a custodial sentence but rather give an alternative of a fine on the grounds that the accused had never had any criminal record before; and that she had ‘contributed significantly’ in collecting much needed revenue for the Government whilst serving as Minister of Fisheries and Marine Resources.

The presiding Judge sentenced the accused to a fine of thirty million Leones (about U$D7, 000) per count; totaling a hundred and fifty million Leones for the 5 counts or alternately serve a three year imprisonment on each count to run concurrently. After the pronouncement of the sentence, the lead prosecutor, Zimbabwean-born Calvin Mantsebo, asked for the learned Judge to order the restitution of the misappropriated money. In his response, the presiding Judge, Justice Samuel Ademusu, ordered the former minister to pay back to the consolidated fund the three hundred million Leones she had misappropriated. She was given a four week period to pay the fine and restitute the misappropriated money or risk being incarcerated until 2013. In actual fact, the accused is now to pay a total sum of four hundred and fifty million Leones within four weeks if she is to walk the streets a free woman again.

Outside the courthouse, reactions to the landmark court ruling differed from amongst members of the public, interest groups; and not least between the parties to the case. Whereas the lead defence counsel, Blyden Jenkins-Johnston, stated that they (defence) accepted the verdict of the honourable court and that they would be convening a meeting of defence counsels to ascertain whether or not to file an appeal against the conviction; the Commissioner of the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC), Joseph Kamara, at a press conference convened immediately after the judgment was less gratified of the ruling. According to the ACC chief, the fine imposed by the court was not commensurate to the offence committed by the accused. He furthered that he would have preferred a custodial punishment and not only a fine; but however, stopped short at questioning the integrity of the court.

The trial has ended at least for now, although there are talks of the defence filling an appeal once it has thoroughly digested the ruling of the learned Judge. The said trial generated much controversy from all walks of life in which conspiracy theories overwhelmed logical reasoning. Behind the scene, there were allegations of judicial intrigues thus leading to the initially assigned Judge, Justice Nicholas Browne-Marke to recluse himself from the trial and Justice Samuel Ademusu brought in his stead. In political circles, there were charges of infighting between and amongst political rivals within the ruling All People’s Congress (APC) party during which fisticuffs sometimes triumphed over debate. There were instances when the courthouse was besieged by people alleged to be supporters of the ruling APC party and who were in ‘sympathy’ with the accused. Even members of the fourth estate were preoccupied with war of words over this law suit; their writings were their arms, and their targets were the conscience of the unsuspecting populace. The whirlwind of the trial did not spare the former Anti-Corruption czar, Abdul Tejan-Cole, who abdicated his position under controversial circumstances.

Be that as it may, though, there is good radiance from this high profile judgment. The judiciary, for its part has not only taken a bold step in the fight against corruption, a virus that has invested almost every facet of the body polity of our society; but has also demonstrated that it has integrity to jealously guard by upholding and maintaining the rule of law irrespective of probable arm twisting from powerful forces, be it overtly or covertly. As for the Commission on its part, the judgment will not only boost its morale but will also help increase public confidence in the work of the Commission; an incentive that is of no less importance if it is to measure up to its statutory mandate of turning back the hands of time on corrupt practices in this republic.

by ibakarr | Aug 11, 2016 | Uncategorized

On 29 and 30 October 2010 in The Hague, hundreds of experts, lawyers and academics met for a conference held by Open Society and the International Criminal Court on Pillage of Natural Resources. All the participants stressed the importance of punishing perpetrators who committed pillage, which is recognized as a distinct crime by the Geneva Conventions, the Statute of the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), the International Court for Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Court (ICC).

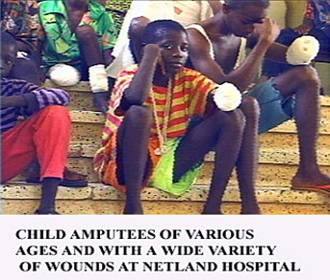

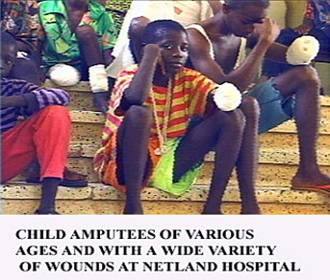

While the world witnessed the tragic visible consequences of the other many war crimes in Sierra Leone, whether it was the child soldiers, the bush wives and victims of sexual slavery, the amputees or those forced into slavery to mine for diamonds, the crime of pillage was also prevalent and the country is still suffering the consequences of thousands of rough diamonds that were stolen from the mines of Sierra Leone and sold abroad. Sierra Leone and its citizens still pay the price of this pillage, which fuelled the war and allowed the rebels to continually remain well armed as late as mid-2001. In short, a country and its people were stolen from.

Therefore it was legitimate to expect that the Prosecutors of the SCSL would prosecute specifically the exploitation of Mineral Resources from the diamond mines in Sierra Leone and indict not only those who extracted and smuggled the diamonds out of Sierra Leone, but also those who sold them in Europe and made their fortune with them.

Today, as we are only months away from a verdict in the last case of the SCSL, we are forced to make this bitter assessment: While the SCSL Prosecutors based one of their theories of joint criminal enterprise (which is not a crime but a mode of liability) on the exploitation of diamonds, they never indicted anyone specifically for the pillage of mineral resources, and none of the ones who were in charge of selling the stones outside Sierra Leone and Liberia were ever indicted. The only form of pillage which has been prosecuted by the SCSL has been the theft of private property of civilians. Of course there are many explanations for this, not least of which was an international community that was supportive in rhetoric of comprehensive justice but put few resources or effort into supporting prosecutions of the economic actors involved in the conflict including diamond traders and certain arms traffickers.

What can still be done to remedy this regrettable state of affairs? As the international court in charge failed on that regard, our hope now lies with national courts. Many National authorities in the Western world have jurisdiction, and therefore could, and should prosecute some of the foreign perpetrators who smuggled the stones out of this continent. Likewise, the criminal courts in Sierra Leone should start thinking about prosecuting some of the foreign actors who are responsible for pillage in the districts of this country.

Even if it is unlikely that these proceedings would give back to the State of Sierra Leone the thousands of rough diamonds stolen, it would be an important step against impunity in Western Africa and the continent as a whole. Punishing those who acted sometimes behind the scenes, in the shadow of economical transactions, is as important as punishing those who pulled the trigger or wielded a machete. For whether it was a civilian’s private property or the riches of this country, Sierra Leone was stolen from and this injustice remains. Sierra Leone today still bears many scars of the war. The international community has acted to address some of these. But this great theft of the country’s natural resources shamefully remains unaccounted for.

by ibakarr | Aug 11, 2016 | Uncategorized

Background[1]

Sierra Leone has less than 200 practicing lawyers, almost exclusively deployed in the capital city, and a population of over five million predominantly dispersed in rural areas. Seventy percent of the population are unable to access the formal justice sector[2] which was virtually destroyed during the bloody decade-long civil conflict. The country’s informal/traditional justice sector, to which the majority turn, is plagued with perennial problems of abuse of authority, corruption and overreach.

Sonkita Conteh Esq

In the face of these challenges, lack of access to justice, in both the formal and traditional sectors is a lived reality for many, particularly the poor and marginalised. Opportunely, the government and civil society are now teaming up to address the problem of lack of access to justice. In its justice sector reform strategy[3] the government made the provision of ‘primary justice’ i.e. justice at the community level, a priority and identified as crucial, the need to make ‘alternative systems for delivering justice’ function properly and effectively with emphasis on strengthening supervision of these alternative mechanisms.[4] Perhaps of utmost significance is the recognition by the government that partnership with civil society on both the supply and demand sides of justice is crucial to attaining its objectives. Hopefully, this move will ensure that the resources of civil society will be deployed alongside available state resources in a strategic manner to meet the justice needs of the people.

Partners in justice

Partnership between the government and civil society is envisaged on two fronts. On the supply side, civil society and the government will undertake capacity building training for chiefs at the community level to ensure among others that these local authorities understand the scope of their authority and not exceed their jurisdiction, women and juveniles in conflict with the law are given a fair hearing and that punishments are not excessive.[5]

On the demand side, the government in partnership with civil society is considering how it can support users of the justice system through ‘the provision of widely available community-based paralegals.[6] Towards this end, the government plans to utilise the expertise and extensive experience of civil society organisations like Timap for Justice,[7] who have provided rural communities with free legal advice and assistance, mediation services and rights education for several years through community-based paralegals.

Scaling up grassroots justice services

Since August 2009, the Open Society Justice Initiative has been working with the Government of Sierra Leone, Timap for Justice, the World Bank and other civil society organisations, to develop a national approach to justice services, one that includes a frontline of community-based paralegals and a small corps of public interest lawyers. Key objectives of this five year project include:

- Working on development and adoption of new legislation to recognise paralegals as providers of justice services, and set standards for paralegals and justice service organisations.

- Assisting in the establishment of national oversight mechanisms as necessary for their formal recognition.

- Establishing a training program for paralegals, and lawyers/ administrators on how to support and supervise paralegals.

- Funding and coordinating provision of justice services by new and existing paralegal organisations across the country.

- Developing and implementing mechanisms for monitoring and evaluation of the work of justice service providers.

Progress and challenges

Within the past twelve months, the scale up project has taken significant strides towards achieving its objectives. In particular it has:

- Formed justice service organisations into an informal coalition to advocate for the inclusion of paralegals in the draft legal aid bill as legal aid providers, and provided written and oral submissions to help shape the draft bill.

- Developed a curriculum and conducted a seven week training course for the first set of 41 community-based paralegals within the scale up project.

- Overseen the deployment of the recently trained community based paralegals in sixteen new offices across rural communities through partner organisations.

- Initiated dialogue with the University of Makeni to host a distinctively tailored and accredited certificate course in paralegal studies to meet the requirements of the project.

- Raised awareness about the role of paralegals in the justice sector through newspaper and newsletter publications in Sierra Leone.

- Engaged influential stakeholders such as the bar association and the judiciary on the utility of paralegals as primary justice service providers.

Several challenges were apparent from the outset of the initiative and remain. These include:

- The rather weak capacity of in-country civil society, particularly those involved in justice service provision in rural areas

- Communication infrastructure in rural communities is particularly poor making it difficult and expensive to reach those in need of justice services especially in the rainy season

- Accessing more resources to sustain the project beyond the five year time line.

How will the project contribute to the legal empowerment of the people?

- The scale up will provide justice mechanisms in communities unreached presently, helping to reverse the access to justice deficit.

- The scale-up will provide an opportunity for communities to benefit from education and awareness-raising on important aspects of the law and basic human rights.

- Community organising as part of the work of paralegals will give communities a voice to participate in decisions affecting them.

Monitoring and evaluation

Community-based paralegals within the project are backstopped by a small corps of lawyers who in intractable cases employ litigation and high-level advocacy to address injustices which the paralegals cannot handle on their own. At a lower level, lead paralegals in charge of several regional offices provide close supervision of the activities of paralegals. Several tools have been developed to aid supervision, such as case intake forms, activity and action ledgers, etc, all of which provide verifiable information about steps taken to deal with cases that are reported. In addition, community oversight boards, comprising members of the communities in which paralegal offices are situated, provide another layer of oversight.

The project is currently considering different evaluation mechanisms to measure the impact of the scale up. One is case tracking, which involves taking a random sample of cases from across the dockets of partner organisations and interviewing all the parties involved. Another method being considered is a survey of households within a certain radius of paralegal offices to gauge perceptions and satisfaction. The scale up team is however open to consider and still studying other methods that would give a better and more holistic picture of the impact of the project in the lives of the rural population.

[1] First published in the JUSTICE-ILAG Legal Aid Newsletter September-October 2010

[2] Government of Sierra Leone Justice Sector Reform Strategy and Investment Plan 2008-2010, pg. vi.

[3] See 1 above.

[4] See 1 above.

[5] See 1 above, pg 18.

[6] See 4 above.

[7] A local non-governmental organisation in Sierra Leone set up in 2003 with support from the Open Society Justice Initiative.

by ibakarr | Aug 11, 2016 | Uncategorized

The obligation to disclose materials in International Tribunals is centred towards having fair trials and upholding the rights of parties engaged in a course of action. However, the need for disclosure should be subjected to close examination by judges, prosecutors and defence alike. In spite of numerous decisions from the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL) granting or dismissing motions for disclosure of materials by both prosecution and defence, difficulties still arise as to what should be disclosed and who has the obligation to do so. Such difficulties recently arise in the closing phase of the case for the defence in the trial of former Liberian president Charles Taylor, when they requested that the prosecution should disclosed all materials relating to payment made to potential defence witnesses whom the prosecution had earlier on contacted. This will not only bolters their case on allegation that the prosecution has been giving incentives to witnesses, but will points to the prosecution’s lack of discharging their obligations with regards disclosing materials to the defence. Is the prosecution obliged to make all materials available to the defence, be it exculpatory or otherwise? Or is the defence in turn has such responsibility of disclosing all materials they intend to use during their case? Or can they incriminate themselves by making available document they have come in contact with during investigation and which can be of assistance to the prosecution? While the latter question seems rhetorical, and potentially damaging, answers to the former ones can be demanding as they might seek to avoid trial by ambush, thus protecting and upholding fair trial rights. Unequivocally, this work seeks to restate the provisions of disclosing materials at the Special Court for Sierra Leone and what responsibility a party has.

The law governing the disclosure of materials at the SCSL is encapsulated in Rules 66, 67, 68 and 70 of the Court’s Rules of Procedure and Evidence (The Rules). The provisions are existing rules covered by other International tribunals that paved the way for the SCSL. Rule 66 provides for the prosecutor to disclose copies of all materials intended to be used throughout the case. Further, the defence can request for permission to inspect documents in the prosecutor’s custody which will be relevant for the preparation of their case. Rule 68 provides for the disclosure of materials which point to the innocence or will attempt to vindicate an accused. Simply put, the prosecution is under an obligation to disclose any material that is said to be exculpatory. The rule also guarantees the continuous obligation on the prosecutor to be disclosing such materials to the defence at any stage during proceedings. Despite these obligations on the prosecutor, must relevantly, Rule 70 may inhibit other provisions which guarantee disclosure if the source of the material is confidential. Thus it appears as if rule70 can override all disclosure obligations especially the continuing obligation of disclosing exculpatory materials to the defence, as long as the prosecution can establish that the material was obtained confidentially and the party has not consented into disclosing such materials. It follows that materials that the prosecution may not want to disclose would simply be placed under this category. While the rules are silent with regards the veracity of such claims, the trial Chamber has been exercising a fair degree of discretion on how to deal with such novelty questions.

The defence is obligated to disclose materials that amount to special evidence in so far as their case is concern. Specifically, Rule 67 provides for the defence to notify the prosecutor of its intent to enter the defence of alibi that is, claiming that the accused was not present at the scene where the crime was allegedly committed, in which case they will be required to disclose any material relating to the suggested location of the accused.[1][2] Remedy for breach of responsibility however differs from case to case. Theoretically, in ensuring effective disclosure, the Rules placed the responsibility on the defence to provide the prosecution with a case statement, setting the nature of their case and matters they tend to challenge in the prosecution’s case.[3] Notwithstanding this responsibility, there can be situations were in parties may not be clear as to their disclosure obligation. Further, materials relating to any special defence, such as insanity or lack of mental responsibility should be disclosed to the prosecutor. On the other hand, the Rules clearly impose the obligation on the prosecution to disclose all materials in its possession, save for those that come under rule 70. Whilst the Chamber can exclude evidence that has not been disclosed to the defence, the defence has the liberty to rely on special evidence even in situations where it has not been disclosed to the prosecutor.

The SCSL in earlier decisions has attempted to explain the underlying principle behind rules of disclosure and what is expected of applicant or respondent. Firstly, all parties are presumed to be acting with a reasonable degree of honesty, thereby placing them under the obligation to do what have been prescribed in the rules with regards discharging their obligation as to disclosure what will assist opposing party in the preparation of their case. In an event where a party acts contrary, the court can subsequently determine what materials can be disclosed under Rule 66, 67 and 68, or which materials cannot be disclosed pursuant to the provisions of Rule 70. In exercising this discretion, the Chamber has noted that the rights of the accused as enshrined in Article 17 of the Court’s Statute, should be necessarily protected at all stages of the trial. Chief among these is the right for adequate preparation, and disclosure forms the basis for such. To ensure adequate preparation, the accused must know the case that has been brought against him and he must be given sufficient time to prepare his defence. By disclosing materials to the defence, he can learn the nature of the case against him and consequently prepare his case.

In assisting the defence, Rule 68 also provides for the prosecution to further disclose materials that points to the innocence of an accused. Such evidence includes those that an accused can use in his defence in a bid to exonerate himself. Dramatically however, the prosecution determines what material amounts to exculpatory evidence. For the defence to make a successful application for disclosure where it appears that the prosecution has failed to disclose, they (defence) must establish that the requested materials are in the custody of the prosecution. However, it is inadequate to only say that the prosecution posses materials that are exculpatory and has reneged on their responsibility to disclose them. The defence must show with certainty the materials that are exculpatory and how they will establish the innocence of the accused.[4] Again this standard should be met in all matters regarding disclosure. There must be particularity with regards the materials being sought for disclosure and also what potential benefits a party is likely to have. Also, since the Chamber has discretion in determine materials for disclosure, for the defence to succeed, it must show that the prosecution has not acted in good faith and that by not disclosing, the accused may suffer undue and irreparable prejudice.

Exculpatory material has however not been a common future before the SCSL. The OTP has claimed to have been disclosing exculpatory evidence under Rule 68 but have largely been done in confidentiality, with the referred materials not been disclosed to the public. Other legal tussle relating to witness statement, interview notes and other documents in the prosecution’s possession have formed a larger part of the disclosure jurisprudence at the SCSL. In spite of its numerous decisions, a contending issue with respect to material that can form the subject for disclosure still looms. In addition to the prosecution’s responsibility of determining what amounts to exculpatory evidence and what in a given circumstance can form the subject for disclose, Rule 70 can override disclosure obligations. It provides for the prosecution not to disclose materials that have been obtained from a private source, except with the consent of such source. Arguably, prosecution may withhold materials and invoke the provision of rule 70. Nonetheless, if the defence can establish that such materials are in the possession of the prosecution and their sources are likely to be public, they can apply for disclosure. Applicable jurisprudence guarantees the defence can succeed if they can establish the availability of tangible evidence whose source would not require consent for disclosure and that such is in the custody of the prosecution.[5] Consequently, in as much as the rule provides for non-disclosure of certain materials the prosecution only have the onus to protect the source if that source has requested that the information or material be kept confidentially. Thus they cannot elect to shield their disclosure obligation by claiming that materials are from a confidential source and cannot be disclosed without the prior consent of the source.

Conclusively, the provisions of Rules 66, 67, 68 and 70 should be read concurrently with the provision of Article 17. The rights of an accuse should be protected and any issue that will cause irreparable prejudice with respect to the ability of the accused to adequately and effectively know about the case against him and subsequently prepare his defence, should be avoided. Protecting a source of information might be minimal with respect to the importance of the information for the exoneration of an accused. Defence however has the onus to get consent from confidential sources in order to pursue applications for exculpatory evidence. While the provision of Rule 70 should be adhered for respect of confidentiality, there should be a balance of disclosure obligation to show respect for fair trails and upholding the rights of accused persons.

[1] See SCSL Rules of Procedure and Evidence as amended May 2010 ( Rule 67)

[2] See SCSL Rules of Procedure and Evidence as amended May 2010 Rule 67 (B)

[3] See SCSL Rules of Procedure and Evidence as amended May 2010 Rule67 (c)

[4] See Prosecutor v Sesay, Kallon and Gbao, SCSL-04-15-T Decision on the Motion for Inspection of Witness Statement (Rule 66(A)(iii) and/or order disclosure pursuant to Rule 68

[5] See Prosecutor v Sesay, Kallon and Gbao, SCSL-04-15-T DECISION ON SESAY APPLICATION FOR DISCLOSURE PURSUANT TO RULES 89(B) AND/OR 66(A)(ii)

by ibakarr | Aug 11, 2016 | Uncategorized

Sierra Leone operates a two tier justice system: the formal and informal system. The formal system deals with matters of general law whereas the informal system is mainly preoccupied with issues arising out of customary law. The formal court system which applies principles of general law is mostly practiced in the Western Area, whereas the informal court system which is largely preoccupied with administering customary law is only applicable in the provinces. The informal justice system, also known as the local court system, has limited jurisdiction to hear and determine both criminal and civil cases. It also has original jurisdiction to hear and determine all land matters in the provinces as a court of first instance. As a result of the jurisdiction of the local court, though limited to a very large extent, and other advantages ranging from cost effectiveness to quick dispensation of matters amongst others, it is widely used by the overwhelming majority of residents in the provinces as a means to settle legal disputes. However, on the low side of it, it is fraught with a number of challenges including abuse of authority which has serious implications on the workings of the machinery of justice in the provinces.

Local Courts are presided over by chairmen who are appointed by the Minister of Internal Affairs, Local Government and Rural Development on the recommendations of the Paramount Chiefs to hear and determine cases brought before them fairly, impartially and without fear or favour. Upon appointment to office, they are sworn on oath to do right to all manner of people as provided for in section 15 of the Constitution of Sierra Leone and according to the laws and customs recognized by such court without affection or ill will. However, this underlying principle for dispensing justice is not so in many local courts in the provinces. This article will seek to highlight some instances of blatant abuse of authority with a specific focus on that of the chairman of Local Court II in the Kakua Chiefdom in the Bo district and its implications on the administration of justice in the said chiefdom.

Local court Number II appears to be adjudicating on matters beyond its jurisdiction. It has been observed that principles of impartiality and professionalism are lacking during court proceedings as there are instances where the said chairman openly flaunts his support for a party in a case before him. In three different cases brought before him, the chairman exhibited bias against either the plaintiff or the defendant contrary to the expressed provisions of the Local Court Act, 1963 (as amended) which prescribes the extent and limits of their powers. This overt abuse of authority that the chairman often demonstrates has caught not only the attention of the general public but even his colleagues some of whom are assessors in the said court including the court clerk.

During the period between February and March this year, three cases were heard in Local Court II that underscores the point of abuse of authority by the chairman. The cases are: Martha Jakema v Ansumana Bangura; Ansumana Bangura v Madam Musu; and Fatmata Kaitibie v Suwu Ngumbu. The first case is about an alleged insult of the plaintiff by the defendant; the second is a case of the defendant using concrete blocks belonging to the plaintiff without the latter’s consent; and the third is an alleged innuendo of the plaintiff having an extra-marital affair. During the said hearings of the first and second cases, the chairman demonstrated consistent bias particularly during cross-examination against Ansumana Bangura who happened to be the defendant and plaintiff in the first and second case respectively. The chairman was unethical and unprofessional in the way and manner he directed his questions at Ansumana Bangura as most of the questions posed were not relevant to the instant cases. Even the witness of Ansumana Bangura was not spared by the unhealthy tactics of the chairman. His questioning of the witness was more or less to implicate her rather than her evidence helping the court to administer justice impartially. For instance, the witness was asked if she knew the number of blocks the defendant used to construct her fence; or had the plaintiff ever reported the defendant to an area chief in respect of the former’s broken blocks; or were these blocks now with the plaintiff before reporting the defendant?

If these questions were not intended to have the witness commit perjury, and thereby discrediting her evidence, how would she know the amount of blocks used by the defendant; or why ask a witness if the plaintiff had earlier reported his case to an area chief? In fact, besides the method of questioning of Ansumana Bangura and his witness, the chairman’s conduct in open court during the hearings were worrying to say the least. His body language, gesticulations and movements in court were circumspect of bias in favour of Martha Jakema and Madam Musu, both daughter and mother respectively. Instances abound were Martha Jakema, in company of a male relation were severally seen surreptitiously entering into the office of the chairman after court hearings. What they did in the office when the matter was sub judice can be anybody’s guess.

In the third instance, that is, in the case between Fatmata Kaitibie v Suwu Ngumbu bordering on an alleged innuendo of the plaintiff having an extra-marital affair, the chairman did not disappoint again in abusing his authority to the chagrin of even the court assessors. The evidence adduced during the hearing showed persistent corroboration in underscoring the fact that the defendant did make the innuendo repeatedly. At the end of the hearing, three of the five assessors jointly came up with a guilty verdict against defendant, Suwie Ngumbu. However, in total disbelief, the chairman dissented; and drew from his pocket a handwritten judgment of the said case which he read to the court. But there was something suspicious about the chairman’s handwritten judgment. The handwriting was very similar to an excuse letter written earlier by the defendant to the court. By that action, the chairman usurped the lawful duty of the clerk of the court to register all orders and judgments of the court as stated in section 8(1) of the Local Court Act, 1963 (as amended). The undue influence of the chairman has greatly disturbed particularly the three assessors including the court clerk who have vowed to report this displeasing attitude of his to the customary law officer, Monfred Sesay.

The chairman’s actions in all three cases under consideration are in contravention of section 42(1)(b) of the Local Court Act, 1963 (as amended) which provides that any member or officer of any local court who corruptly favours or disfavours any person shall be guilty of an offence. In fact subsection (3) of same specifies the appropriate punishment of either a fine or imprisonment or both for those who are found wanting. As an alternative, section 5 of same provides that the local government minister or any person or body authorized by him may dismiss or suspend any member of a local court who shall appear to have abused his authority. What is unfortunate though is that most of the local court users have little knowledge about these legal provisions that would equip them to fight cases of injustice.

Concluding therefore, it is important to note that such outright abuse of authority is a threat to justice in the informal court system. It undermines the confidence reposed in it by especially the poor, marginalized and vulnerable people who are in the majority. The actions of the said chairman need to be nipped in the bud before it becomes unbearable. As such, it is but fitting that a judicial committee is set up to be looking into cases of such nature and where necessary, punitive measures such as fines, suspensions, and or dismissals are instituted against those who act contrary to the provisions of the Local Court Act, 1963 (as amended). Such a mechanism will help greatly curb abuse of authority with impunity thereby consolidating the rule of law in local courts.